Workplace safety practices have changed, but the need for an AED hasn't

Workplace safety initiatives have changed during COVID-19, shifting to focus on keeping employees safe from the virus and implementing programs that ease the stress of transitioning back to the workplace. Recognizing that many people don't feel safe visiting public spaces, safety leaders are investing in personal protective equipment (PPE) such as face masks, hand sanitizer, and gloves, as well as creating physical barriers to reduce the spread of the virus.

Although traditional workplace safety programs may not be top-of-mind for many organizations in the age of COVID, it's more important than ever to plan and prepare for the possibility of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) occurring in the workplace or the community.

An increase in OHCA

Globally, there has been an increase in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) cases, which is directly related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many areas have reported that the rate of OHCA is 2-3 times higher than during the same period in 2019.1-2 This increase is in part due to patients' reluctance to visit a health care provider for fear of contracting the virus. It is also linked to the lingering effects of COVID-19 on cardiac health.

Studies from around the world are reporting a connection between COVID-19 and longer-term effects on the heart. One study performed by the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that 78% of patients who recovered from COVID-19 had ongoing heart abnormalities and 60 percent had myocarditis, which is an inflammation of the heart muscle. Both of these could put patients at risk for complications including heart arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death.3

It's important for workplaces, schools, and community buildings to address all the safety concerns caused by COVID-19. The heightened risk of heart conditions such as SCA for those who have recovered from the virus makes it more important than ever to have an automated external defibrillator (AED) available in public spaces. Early intervention with CPR and an AED is critical to helping an SCA victim before emergency services arrives.

Delays can be deadly

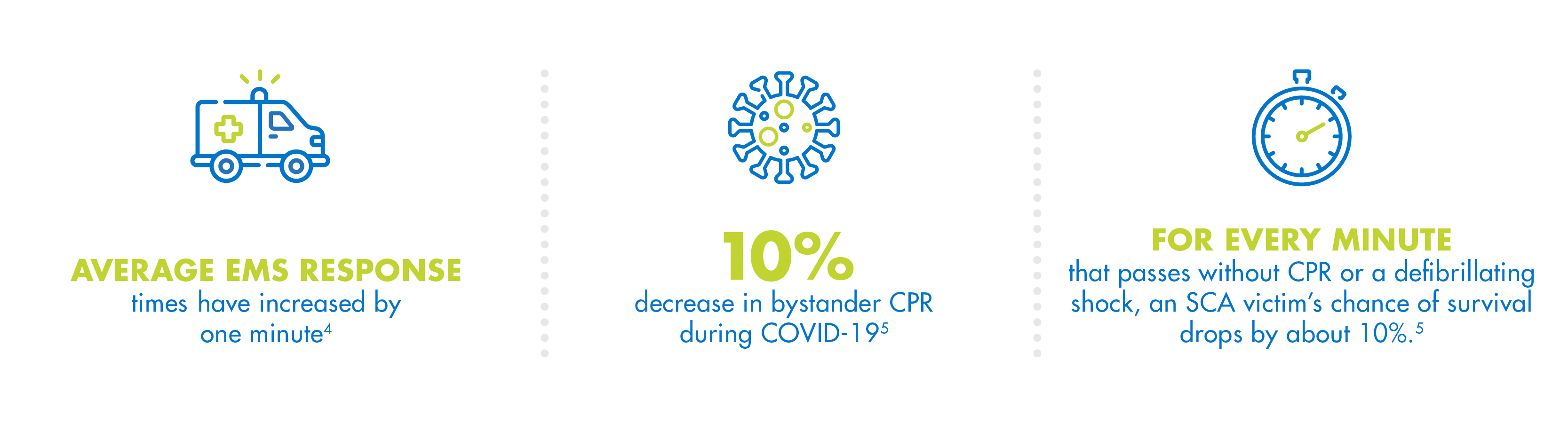

The pandemic has also impacted EMS response times, which have increased due to greater demand on teams and resources.4 Even a one-minute delay in care can decrease a victim's chance of survival by 10%,5 so early intervention by bystanders is especially critical during the first few minutes after a victim's collapse.

Unfortunately, however, studies also show that people are less likely to provide CPR and early defibrillation due to social distancing measures and fear of COVID-19.4 This reluctance to help could make the difference between life and death for a victim of SCA.

Is it safe to perform CPR?

Ensuring that bystanders are prepared to help in the first few minutes of an SCA event or other medical emergency can help save a life. For that reason, it's essential to educate people on how they can safely provide life-saving CPR during COVID-19. Both the AHA and ERC Guidelines recommend providing hands-only CPR.

Although hands-only CPR does not involve any direct face-to-face contact between the rescuer and the victim, rescuers should cover their own and the victim's mouth and nose before delivering CPR. If possible, rescuers should also use protective gloves.

For a victim of OHCA, the best chance of survival depends immediate, high-quality CPR and a defibrillating shock from an AED. All ZOLL AEDs include real-time, guideline-driven CPR feedback, empowering lay rescuers to help a sudden cardiac arrest victim during the first few minutes after collapse. ZOLL AEDs also include a face shield and protective gloves for use during the rescue.

In the time of COVID-19, it is more important than ever for organizations of all types to plan strategies that mitigate the risk of SCA. Take the time to learn about SCA, CPR, AEDs, and the importance of early bystander intervention. In the chain of survival, early intervention with CPR and an AED could make the difference between life and death.

1 Holland, M., Burke, J., Hulac, S., Morris, M., Bryskiewicz, G., Goold, A., ... & Stauffer, B. L. (2020). Excess Cardiac Arrest in the Community During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Jacc. Cardiovascular Interventions, 13(16), 1968.

2 Lai PH, Lancet EA, Weiden MD, et al. Characteristics Associated With Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrests and Resuscitations During the Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic in New York City. JAMA Cardiol. Published online June 19, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2488

3 Puntmann VO, Carerj ML, Wieters I, et al. Outcomes of Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Patients Recently Recovered From Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol. Published online July 27, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2020.3557

4 Uy-Evanado A, Chugh HS, Sargsyan A, Nakamura K, Mariani R, Hadduck K, Salvucci A, Jui J, Chugh SS, Reinier K, Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Response and Outcomes During the COVID-19 Pandemic, JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology (2020)

5 2010 AHA Guidelines for CPR and ECC. Circulation. 2010;122:S706.

6 Mitchell S. V. Elkind, M.D., MS, FAHA, FAAN, president of the American Heart Association (AHA)